Stay tuned for my second blog post from the passage in the next few days. There will be thrilling accounts of fires and steering failures, a sketch of what a “typical day” looks like on the Rascal during long passages, as well as my recipe for the Tropic of Capri-corn-dogs that I fried up just after I crossed the line.

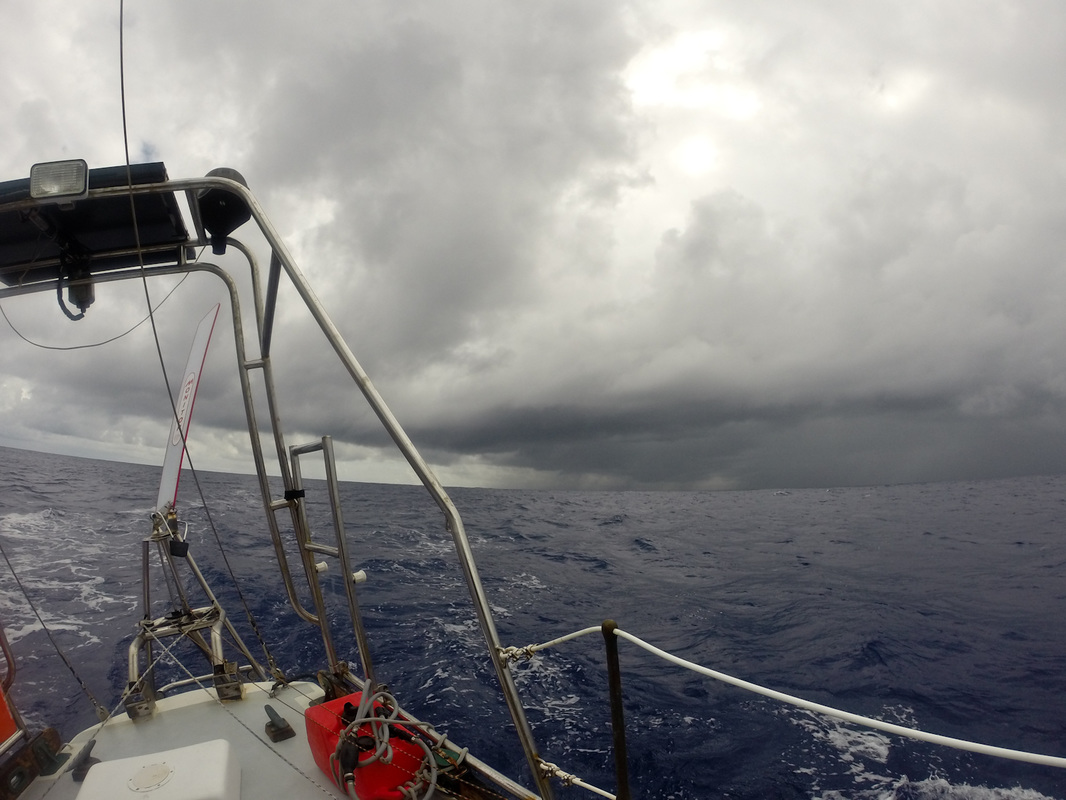

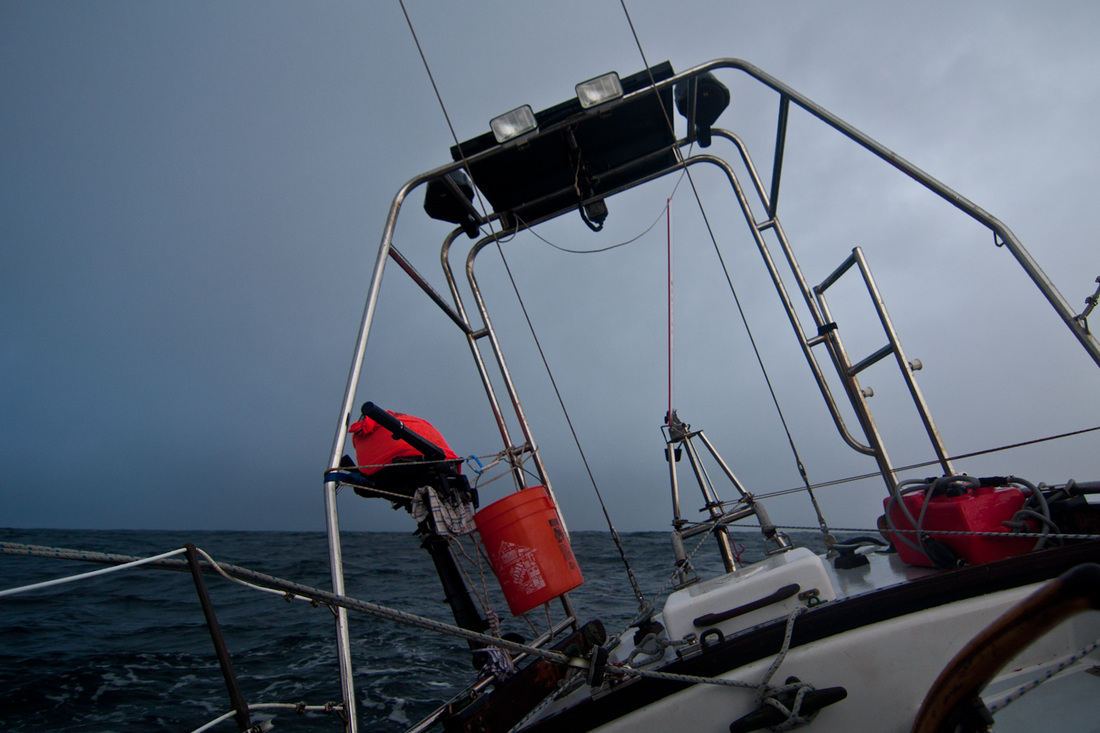

There were three distinct phases of the passage, with very different weather dominating each. The first phase was in the SE trade winds and they were very, very consistent (10-25 kts from the SSE, SE, or ESE). The only trouble was that my destination was to the SE which meant that I was bashing into the wind and the waves for the first two weeks. It was also quite cloudy and the decks were awash with rain and waves 24 hours per day. You can imagine how that might be frustrating, but I was well aware of what I was in for and it was actually a very productive portion of the trip in that I managed well over 100 miles per day for 10 days straight. In fact, I went several days without adjusting my course or sails at all. It was definitely rough sailing and I’m fortunate that I’m not the sort to get seasick, because the Rascal and I really took a beating during the first part of the trip. There isn’t much you can do around the boat in such conditions, and I managed to polish off lots of books from the relative comfort of my pilot berth. There were one or two days in the middle that felt particularly hateful, with gusts up in the 30s.

On and on the wind came. It had tremendous force and the whole boat was singing it's song as it whipped through the rigging. She was heeled over at an absurd angle and she bowed over even further with each gust. Yet stronger, and more dangerous, than the wind - was the swell. A very steep, closely spaced set of waves were running and the Rascal was laboring over them like a whipped hound. Her bow plunged into each wave, flinging spray skyward and rocking the captain as if to recall a bronc busting competition. Occasionally, our course, the extreme steepness of a wave, and the treachery of Poseidon would combine to send the Rascal careening off the side of a wave. She'd come down like a cannonball in the following trough and when she did, she let out a shudder as though she was possessed. The captain, similarly, would let out a whimper from his bunk and wonder if it might be a good idea to heave-to until the weather calmed down.

As my time in the Galapagos drew to a close, I got more and more fired up to tackle the passage, but the cold beers and friendly wildlife made it tough to leave.

It was typically quite cloudy, but the moon was bright and sometimes it would break through in the night to shine on the boat. I would wake up, see a bright light, think it was a boat nearby, and leap up into the cockpit only to find the man in the moon beaming down on me with a mischievous grin. This happened several times before I got used to it and I slowly stopped noticing.

Early one morning, at about 4am, I happened to be awake reading my book. It was blowing 25 knots with a substantial rain storm and the Rascal was really rocking and rolling. I looked up from my book and saw a light shining in one of my windows. "Just the ole moon," I said to myself. Except I knew it was totally overcast. So I slowly ambled up to the companionway, and nearly had a heart attack. A HUGE ship was right next to me. The ship itself was probably 300 feet long and it can't have been more than 2-300 yards away. Out there in the middle of the goddamn limitless pacific, I had come within 300 yards of another boat!

He didn't seem to be moving at all and I was doing a consistent 5 kts. By the time I noticed him, I had already nearly passed him and it was clear we weren't on a collision course. I hailed him on the radio several times in a bunch of different languages, but never got any response. I can only assume that he noticed me on his radar and came to check me out. It was of a small tanker size, but I think it must've been a research vessel or a navy boat of some sort, though I can't imagine what he was doing all the way out there. It was pitch black and the boat was rocking around like crazy, but I snapped a few shitty pictures just to prove that it had happened. All you can make out are his navigational lights whipping across my field of view.

This last passage seems like a good illustration (if a bit extreme) of the way I've been living my life over the past year. I've realized that I don't need to burn lots of fuel, I can use the wind to move me. I don't have to take long showers and go through water with reckless abandon, in fact I only used 20 gallons during this whole passage. I don't even really need much space, the 30 feet of the Rascal will do just fine. I think a lot more about my impact on the world around me and if I ever go back to living on land, I'll certainly do it in a more respectful manner. In a way, recalibrating my expectations to my humble life on the Rascal is an incredible gift. I'll be satisfied with so much less in the future and appreciate luxuries that much more.

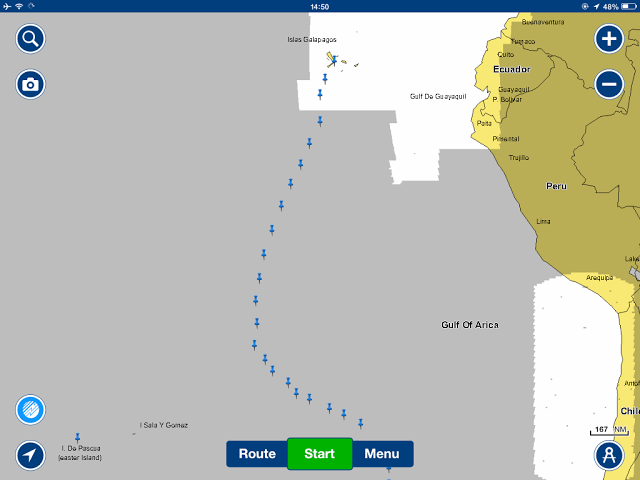

This passage is by far the longest I’ve ever done, with 3524.1 nautical miles covered from door to door and 37 days between my departure from Puerto Villamil in the Galapagos to Puerto Montt in southern Chile. This brings my total for the trip to 9889.8 miles & 355 days of sailing. Just short of 10k and almost an entire year of my life.

To give some perspective, the distance I traveled during these last 37 days is equivalent to the following spans (as the crow flies): Boston, Massachusets to Stockholm, Sweden; Anchorage, Alaska to Acapulco, Mexico; Honolulu, and Hawaii to Tokyo, Japan. Its a damn long distance. Its also equivalent to the Rascal running 155 marathons or 4 marathons per day for five and a half weeks.

Between the calm and the short days on either end of the passage, I averaged 90 miles per day which is respectable but certainly not fast. I think if I were to attempt this passage again, I'd probably stay a little bit further west to try and avoid the high, but chances are that route would see heavier weather on the run in to Puerto Montt.

The course I sailed was about 74% efficient which is quite good considering how much time I had the wind coming directly from my destination. The highest winds I saw were somewhere in the low 30s. The water temperature, over the course of the trip, plummeted from 82 degrees in the Galapagos to 53 degrees in Chile.

There was one point, ten days into the voyage when I was 967 miles from both the Galapagos and Easter Island, and 1100 miles from continental South America (the Peruvian coast). I dare say thats about as far as I'll ever get from land. A thousand miles from nowhere.

I also crossed the Tropic of Capricorn during this trip, which is the southernmost circle of lattitude where it is possible for the sun to be directly overhead. As you travel further south, there is never a day (even in the height of summer) when the sun is overhead. I crossed the Tropic of Cancer (the northern equivalent of the Tropic of Capricorn) in Mexico last June.

I've been in “passage mode” for a long time. After a couple months of long sails, the Rascal and I are both pretty well worked. I'm going to spend the next few weeks making repairs to the Rascal, devising a master plan for my time in Chile, and learning how to walk again. I'm planning to stay in the Puerto Montt area for that timeframe, because it’s the easiest place to get boat parts and there are other voyagers here who have lots of valuable info about the territory to the south. It is the tail end of summer in the southern hemisphere and I’m thinking about doing some traveling around on land while the weather is still warm and pleasant.

My general plan for the winter is to try and find a tasty looking fjord or volcano (of which there are several!) with a snug anchorage at the base of it to see if I can’t manage a ski decent or two from the boat. I’ve got lots of logistics to figure out first (skiing/sailing partners, timing, anchoring equipment, locations, etc) and a lot of my plans will be heavily dependent on weather. At the moment, I’m feeling quite proud of myself for having made it this far and I don’t have any intentions of diving into anything too ambitious in the southern fjords just yet.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed