It felt like a million bucks to finally have my anchor dug into Chilean soil. I had lots and lots of leisure time during the passage, but never absolute relaxation. I was always on duty to some degree. That first night at anchor felt tremendous. I had a little celebration with my last beer, slung my hammock on the front of the boat, and took in a glorious sunset over the farms of Puerto Ingles.

For a country that hasn't fought any wars in a very long time, the Chilean Navy (called "La Armada" which literally means "The Armed") has a very substantial presence. True to form, just five minutes after leaving the anchorage, I found an Armada gunship across my path and heard a hail on the radio. I fumbled my way through a spanish explanation of my situation, who I was and where I was going. It is a requirement for all foreign yachts in Chilean waters to check in with the Armada twice a day via radio, if possible. They were very polite and efficient and I continued on my way towards the neck of the channel.

There were lots of fishing boats working back and forth as well as some cargo carriers headed into the islands. I also got my first tastes of the salmon and mussel farming that is such an enormous part of the economy along the Chilean coastline.

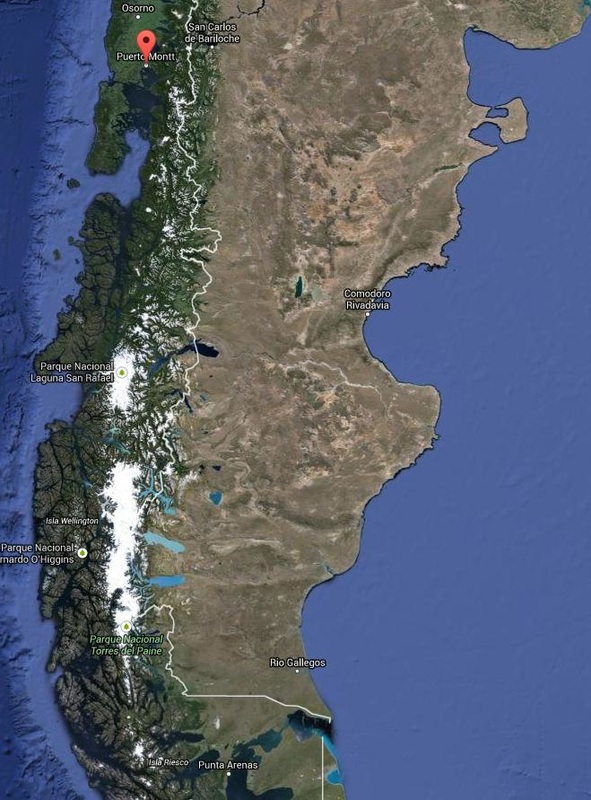

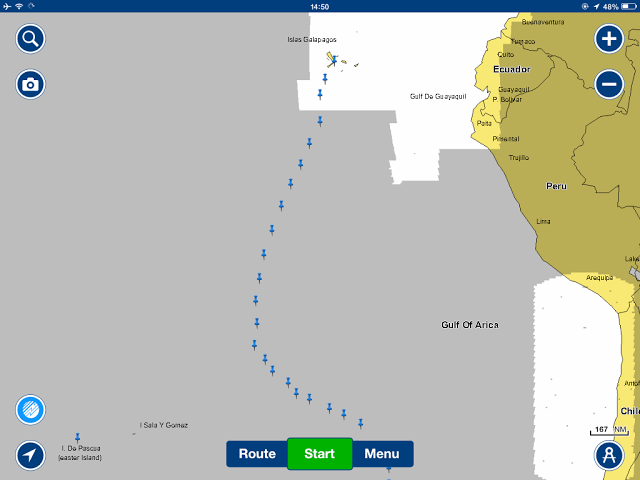

I pulled into the marina around noon the next morning after a short sail and a quick tidying of the boat, and I was immediately met on the dock by a pair of friendly smiling faces! I was unsure of the direct Galapgos to Puerto Montt route in the beginning, but another sailor in the Galapagos had put me in touch with Clint and Reina on S/V Karma who had completed the sail just before me. They had sent me a bunch of info before I left (that was encouraging enough that I decided to sail the direct route) and they happened to be in the marina in Puerto Montt when I arrived! It was my first time talking with people in 37 days and it felt great to be back in civilization! It was also great to be meeting them in person for the first time after all the great advice they gave me for the passage.

I went up to the marina office and started the proceedure of checking into Chile. You need to wait on the boat until customs, immigration, agriculture, and the armada officially allow you to enter, but my friends on Karma offered me a cold beer and waiting around for an afternoon isn't such a big deal after waiting around for 37 days, especially when you're drinking an ice cold Escudo! I also had internet, so I was able to get in touch with my friends and family via skype. All of the government officials that came out to the Rascal were very efficient and friendly and several of them struck up conversations and asked me questions about myself and the voyage.

It was around 9pm before all of the officials were done checking me in, and one of my marina neighbors invited me over for a glass of wine. Richard had all sorts of great stories and info for me. He just recently transited the northwest passage (sailing around the top of Canada!) and is planning to sail his red steel schooner down to Antarctica. Clearly there is a different caliber of sailor down in Chile!

I took the bus into town the following morning (a man I met at the marina gate let me borrow bus fare to get to the bank!) and I finally got my first taste of Puerto Montt.

During those first few days, Clint and Reina really took me under their wing, showing me all sorts of shops around town, introducing me to super helpful people, and answering a huge host of questions. One night, we went to visit some Italian friends of theirs that are cruising around on a gorgeous catamaran. The dinner was spectacular, with homemade bruschetta, glorious Chilean wine, and some Italian empanadas that were to die for. I’ve gotten to hang out with the Italians and their Australian friend several times since then and I’m hoping to do some cruising with them later this winter. They’re all really warm, welcoming people.

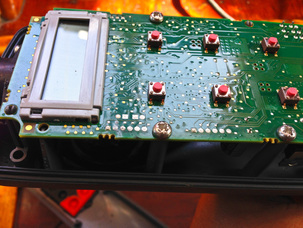

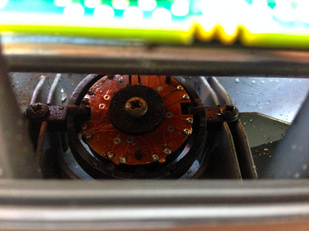

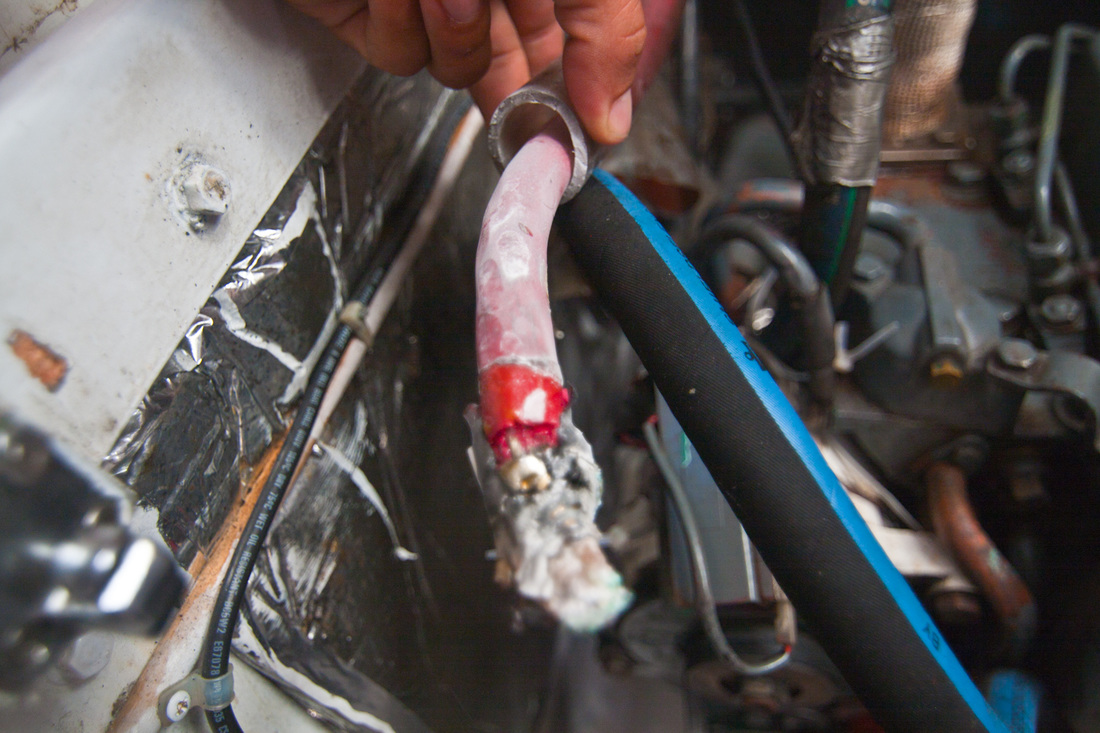

Over the course of the last two weeks, I’ve been able to fix my engine (reassembled the heat exchanger with the proper seals and rewired the starter with appropriate connections and protections) and I had a new part cast and machined for the tiller. There were also a handful of other little projects around the boat, including a malfunctioning auto pilot that was fixed simply by laying out in the sun – a prescription that has been enough to fix me on a number of occasions.

Naturally the first thing I did after hanging up was cracking the unit open. It was immediately clear that the "waterproof" tillerpilot had a bunch of moisture inside. I spent five mintues wiping droplets up with a papertowel and set it in the sun to dry. I assembled it later that afternoon and it worked like a charm - as good as new.

A friend back in the states also put me in touch with a Bucknell grad who has been living down in Chile since we graduated (we were in the same class year, but didn’t particularly know each other back then). Jess lives in Puerto Varas which is a lovely little tourist town beside a lake that is about a half an hour north of Puerto Montt. Puerto Varas seems to have even more German influence than Puerto Montt and it’s a very clean, charming town. From the center of town you can see two enormous volcanoes rising above the lake, Volcán Calbuco and Volcán Osorno. You’ll hear more about them later!

I’d been searching for some way to try and help repay Raul for his kindness and one day he let slip that he’s “getting too old to chop wood”. I happen to love splitting wood, so he gave me a ride to his house one afternoon and I went to work on the pile. While I was chopping, he told stories from his time sailing around in the south and blended up a couple of fresh orange juices. Incredible.

After everything was split down to a manageable size, we went inside and started perusing his vast library of nautical charts. He kept pulling out new charts, browsing over them for a few seconds and then he’d let out an exclamation, “Hey! Look at this island - it has a hot springs right next to the anchorage and towering Alerce trees!” I sat there taking notes as fast as I could and making sure to mark all the best fishing places and anchorages that were free of ice bergs. “My friend Heinrich lives on this peninsula and you can hike up into this canyon with the fisherman’s son!” On and on these inconceivably spectacular tips flowed, until Raul’s daughter piped up from the other room. The volcano was erupting.

We all looked out the window our jaws dropped.

I’d like to think I’ve seen a fair bit of nature in the past year of sailing, but I everything else paled in comparison with this. It was so enormous and felt so totally and completely powerful. Volcano Calbuco was about 20 miles away, yet we could see the ash billowing up as if the peak was right on top of us. Once it hit a certain height, it spread out, and was starting to look something like a mushroom cloud.

Raul made a really poignant comment to the effect of, “In the eyes of the volcano, everyone is the same and everyone is nothing. Fishermen, politicians, welders, policemen, and beggars are all humbled in the face of a force as strong a volcano or an earthquake.” It’s interesting the way a natural disaster like that can erase the differences between men.

Raul decided the safest place for them was on his boat and they dropped me off on their way to the marina. My tiller was still in the shop at this point, so I knew there was no quick way for me to sneak out of town. I grabbed my emergency ditch bag and zipped out in the Superhighway to start taking pictures just as the sun was beginning to set. The entire mushroom cloud of the eruption lit up and slowly changed colors as it built and expanded. Flashes of lightning continually danced around the base of the column. It felt, for an instant, like I was transported back to some ancient time, where the earth was still being formed and dinosaurs were roaming around. Everything about the scene was unreal.

I got back to the boat as night was falling and I got to work rigging an emergency tiller with an axe, some vice grips, and a few voile straps. MacGyver would've been proud! It was ugly, but it was enough to steer the boat.

Jess called me with plans to go up and help with the cleanup effort and I decided to tag along. A big group of her friends showed up, armed with shovels and brooms and we slowly made our way into the ash fall zone along with a bunch of rescue workers and huge military trucks. At first, it just looked a little dusty, but as we got closer and closer, the ash began to pile up. It looked like a big snow storm, with ash covering the ground and a blanket of gray over everything.

I’m leaving today for an exploratory mission into the fjords. I figure it’ll be good to get my feet wet while the weather is still good and I’m still close to the supply / repair facilities in Puerto Montt. I must also admit that I’m really chomping at the bit to dig into the real part of Chile after being in port for a couple weeks.

This trip will also help determine my course for the rest of the winter. I should have a lot better idea of the feasibility of skiing from the boat once I’ve gotten a better look at the terrain and accessibility of snowfields. In addition, I’m planning to catch a few king crabs, soak in a few hot springs, and maybe even drink a couple bottles of wine. Wish me luck!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed